Part 1: Historical Perspective

Many clients are asking about the next market downturn. We consider it one of our primary responsibilities to evaluate “what ifs” for the companies in our portfolios. We make it our job to prepare ahead and make informed decisions about what could hamper the overall economy and stock market.

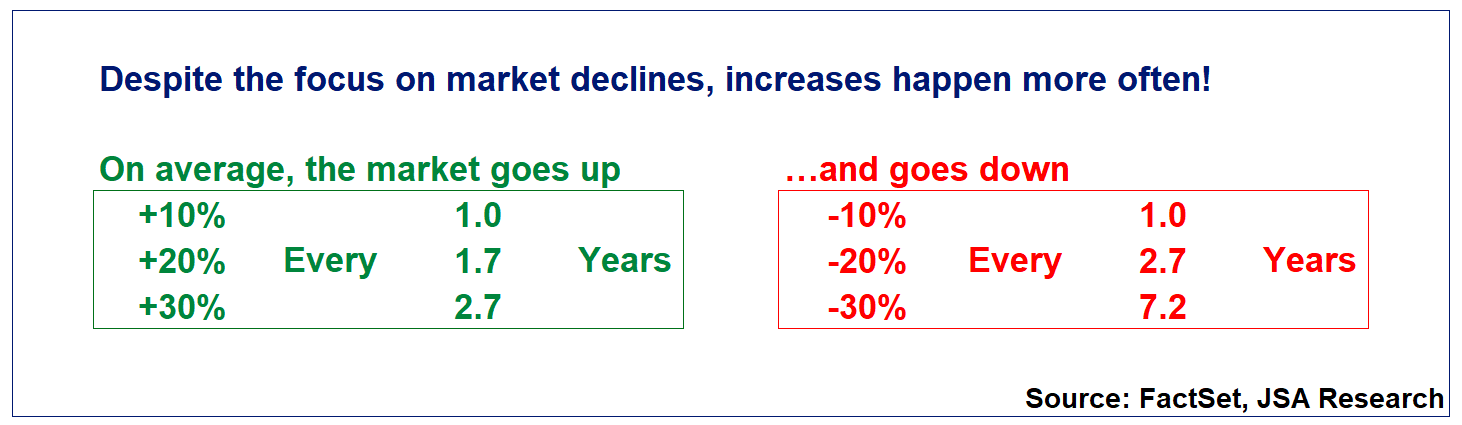

To demonstrate how we think about this, let’s begin with a simple question: How often do market declines occur? Of course, there are different definitions, but generally, investors define a bear market as one where stock prices decline by 20% or more from recent highs. Historically, 20% market declines occur, on average, about every 2-3 years. The table below shows the frequency at which market ups and downs occur.

What can we learn from this?

- Market prices move quite a bit in both directions. History tells us that a 10% market move in either direction happens about once a year. So, if you invest, you must be prepared for stock prices to move more rapidly than you might expect for what a company or market might really be worth. For the last century, however, embracing those ups and downs has been fruitful!

- Despite all the focus on market declines, market increases happen way more often. The table above shows that market increases occur more frequently than market declines of the same magnitude. There always seems to be reasons convincing you to “get out of the market,” but “staying in the market” has been far more profitable.

- When will the stock market crash? Nobody knows when the market will decline, only that it will happen, and that’s OK because knowing what’s happened can help us prepare for the future. So, think about how you’d feel if your portfolio dropped 10%, 20%, or even 30%. If there’s a level where you get uncomfortable, consider that when setting your allocation to stocks & bonds before the actual decline occurs. But, again, preparation and confidence in your plan are critical.

Part 2: Staying Invested

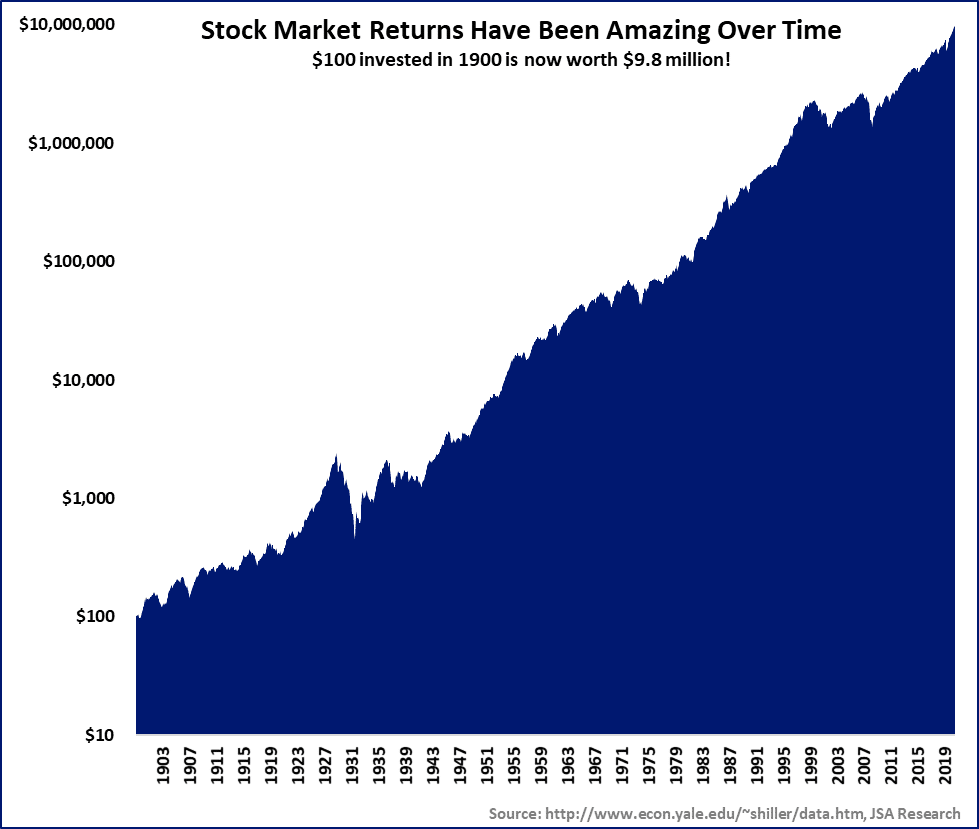

Now that we see how the market fluctuates, why would someone invest at all? In short, it’s the best way we know to accumulate wealth over a lifetime. If you were lucky enough to have a family member invest $100 at the turn of the last century (the year 1900), that is now worth close to $10 million!

This graph includes significant global events—the Great Depression, World War II, a U.S. Presidential Assassination, the Tech Bubble, and the Financial Crisis. Yet, those events look like minor blips in the long-term trajectory of building wealth over a lifetime.

That said, we are mindful of the conditions that can exist before market corrections occur. Those include:

- Investor euphoria. Another way to say this might be over-optimism like we saw in the tech bubble of 1998-2000. While the mechanics of many buyers and few (or no) sellers will push prices higher, there comes a breaking point when eventually no one else is willing to buy and prices decline.

- High stock prices. A rosy outlook of the future usually pushes prices higher. However, that can lead to disappointment (and lower investment returns) if things don’t live up to expectations.

- Monetary Policy Missteps. The Federal Reserve can fuel the economy by providing access to money (low-interest rates). They can also slow the economy by raising rates. However, sometimes their timing isn’t perfect, or their tools aren’t effective, leading to market hiccups.

- Increasing Competition. Industries that do well attract attention, and if there aren’t limits, lots of copycats and others can come into the market. So, in economic terms, supply rises, and demand goes down, leading to a poor investment. While it’s getting to be 15 years ago, a good example is from just before the financial crisis. At that time, easy lending standards led to high demand for homes, which caused home prices to increase, leading to significant home building. But, of course, once it became clear there were too many homes on the market, prices dropped a lot, and the crash began.

- Randomness. In Jeremy Siegel’s book, Stocks for the Long Run (2014), he concludes that, of the 145 daily stock market changes of 5% or more from 1888-2012, less than 25% of them align with a significant world or political event. We like to think of these as akin to an avalanche. Something insignificant or invisible on the surface can shake markets. But it looks relatively random most of the time.

Some of these conditions seem present, or at least possible today. However, even if you get out of the market “on time,” time works against you. You’ll also have to figure out when to get back in, and that’s a tough decision to make.

It’s essential to understand how hard making two well-timed decisions really is. For example, the market peaked on February 19, 2020, as it became evident COVID-19 would significantly impact the global economy. If you timed that well, you avoided a 30%+ decline over the next month. However, if you didn’t get back into the market within six months, you would have missed out—big time. We’ve generally found that it’s MUCH harder to make that second decision as it typically goes against everything you believed in making the first decision!

Part 3: Use Time to Your Advantage

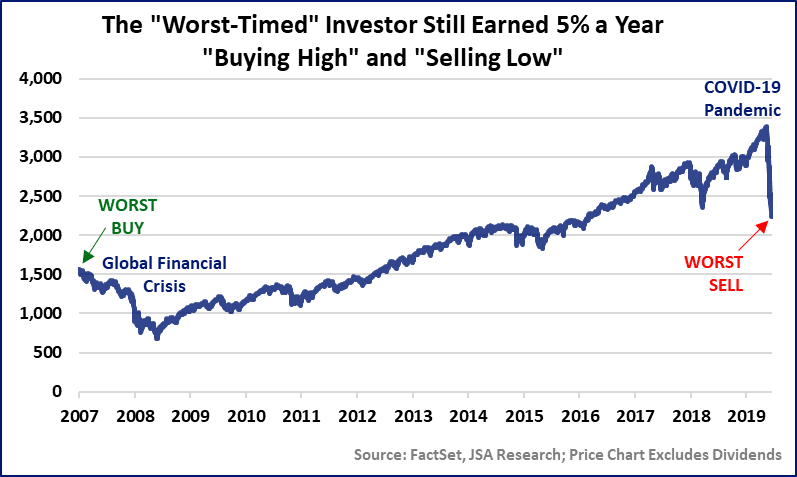

Let’s have a little fun with another question and ask; What would happen if you were the worst-timed investor? That is, you invested your nest egg at the peak right before the financial crisis (October 9, 2007) and sold everything at the bottom of the COVID-19 pandemic (March 23, 2020). Keep in mind that sounds and feels pretty much like the opposite of “buy low, sell high,” right?

However, that doesn’t consider one thing: TIME. As it turns out, time—in this case, almost 13 years, is still on your side. Even “buying high” and “selling low” (yikes), which is the exact opposite of what you want to do, ended up with 86% more money, which works out to about 5% a year. That’s not great, but it’s not bad for what seems to have been terrible timing—time in the market matters.

Key Takeaways

- The longer your time horizon, historically, the better your chances are to build wealth. Market returns on any given day are about a coin flip (U.S. markets have moved higher 52% of days since 1928). But investing for 20 years led to more wealth 99% of the time and doubling your wealth 91% of the time (FactSet, JSA Research). Short time horizon: a coin flip. Long time horizon: excellent odds.

- Expect the market to move a lot in both directions. 10% price moves in both directions happen, on average, about once a year, so don’t let that rattle you. They’re often not even explainable.

- Stay invested. Timing the ups and downs of the market is seemingly impossible. What’s most important is that you have short-term needs invested in safer investments. While we work with all of you to dial this in specific to your financial life, a decent starting point is to have what you’ll need from the portfolio over the next five years in safer bonds and cash. For example, if you expect to withdraw 4% of your portfolio in each of the next five years, put ~20% in bonds & cash and the rest (80%) in stocks. Of course, everyone differs a bit, but the basic concept is a good one.

- Stick to your financial plan. We build financial plans to handle the market’s ups and downs. Therefore, sticking to it is one of the most important aspects of a successful outcome.

Jacobson & Schmitt Advisors, LLC (“JSA”) is a registered investment advisor. Advisory services are only offered to clients or prospective clients where JSA and its representatives are properly licensed or exempt from licensure. The information provided is for educational and informational purposes only and does not constitute investment advice and it should not be relied on as such. It should not be considered a solicitation to buy or an offer to sell a security. The information contained above is for illustrative purposes only.

The views expressed in this commentary are subject to change based on market and other conditions. These documents may contain certain statements that may be deemed forward‐looking statements. Please note that any such statements are not guarantees of any future performance and actual results or developments may differ materially from those projected. Any projections, market outlooks, or estimates are based upon certain assumptions and should not be construed as indicative of actual events that will occur.

All information has been obtained from sources believed to be reliable, but its accuracy is not guaranteed. There is no representation or warranty as to the current accuracy, reliability, or completeness of, nor liability for, decisions based on such information and it should not be relied on as such.

Past performance shown is not indicative of future results, which could differ substantially.